The following film presents the only existing video source on the crossing of the French-German border from 1871 and 1914. This document, kept by the

Institut National de l’Audiovisuel (INA), is a black-and-white silent video clip. This 3-minute film was shot between 1907 and 1914 by a German tourist, most likely coming from Alsace (chapter 5). The video comprises five parts recounting a summer journey from Munster to Gérardmer via the Col de la Schlucht and the peak of the Hohneck – that was major tourist destinations at the Frenc-German border.

In the first part, entitled “Abfahrt von Munster nach der Schlucht“ [From Munster to the Schlucht], the trip starts on the Münsterschluchtbahn – which is the name of the small electrified railway connecting Munster and the Schlucht during the summer. One can see tourists in hiking gear boarding the trolley, walking in the woods or following the road leading to the pass. After the station Alternberg, a cogwheel railway takes over. The video then lays emphasis on “Germany’s highest railway”, as it was advertised at the time. After the Krappenfels tunnel, the film shows the Hartmann chalet, a hotel complex built on the eastern slope of the Vosges after the annexation of Alsace-Lorraine to the German empire. Upon arriving at the pass, one can see cars and other vehicles. They transport the numerous tourists coming from France, Germany or other countries who want to climb the Hohneck (chapter 6).

The second part of the film, “Felspartien bei der Schlucht (deutsche Seite)“ [Rock formations at the Schlucht (German side)], shows some images of the mountains as they could be seen from the German side of the border. Next to a bench set up by the Vogesenclub (Club Vosgien), at the foot of the Rocher du Chameau [Camel Rock], a man plays the barrel organ to entertain tourists.

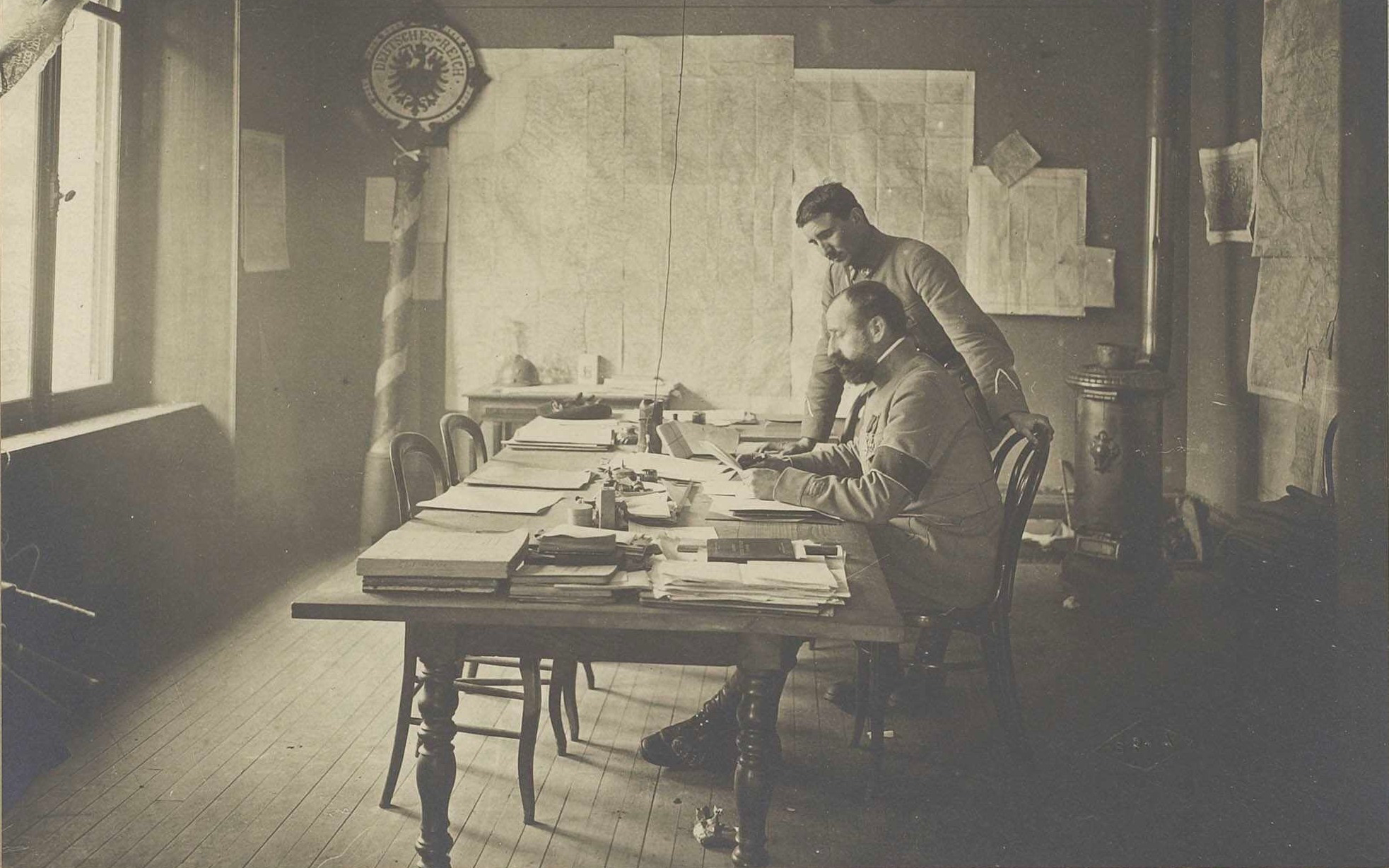

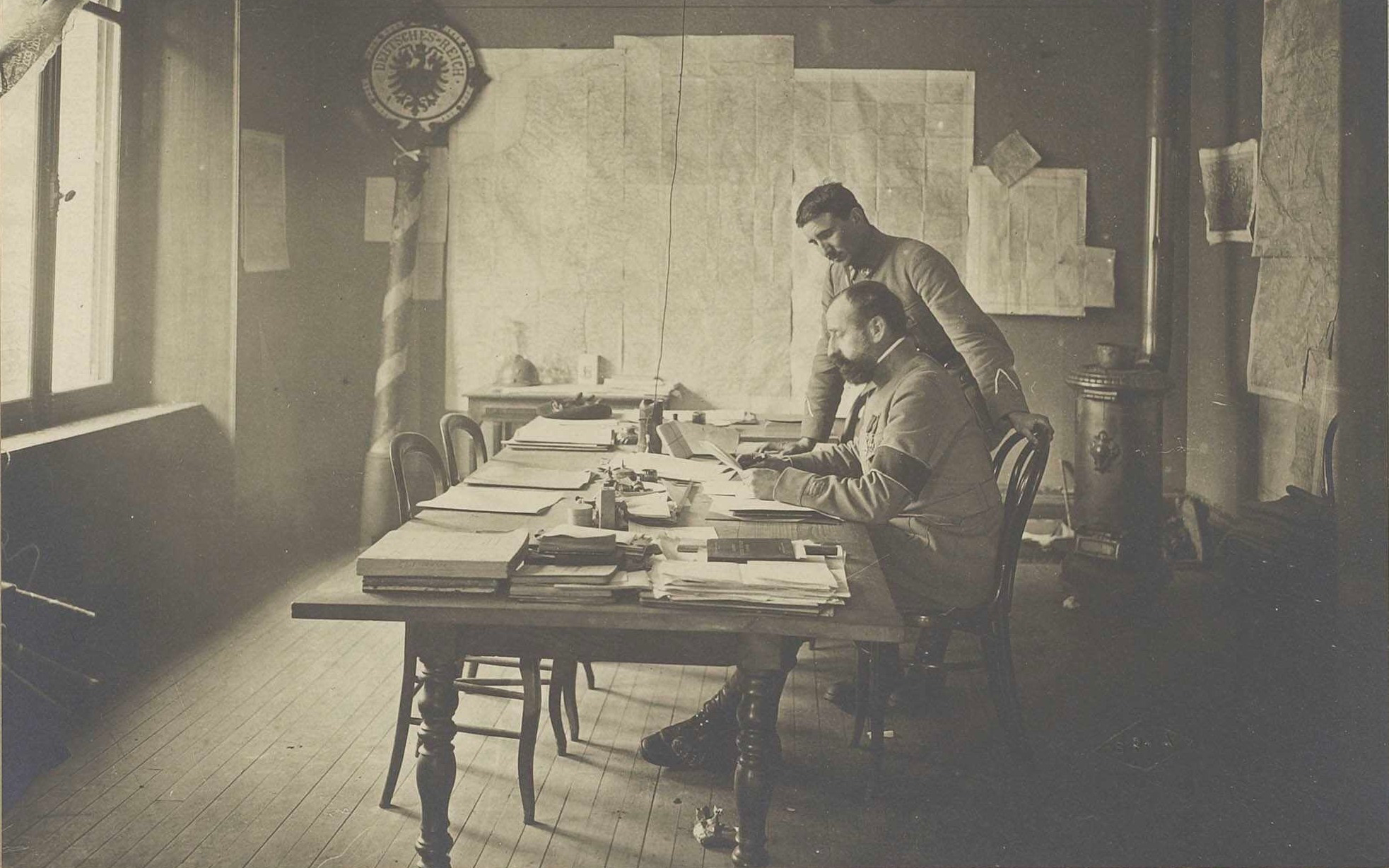

After 1871, the Schlucht became a border pass, and this characteristic is given particular attention in the third part of this short film, “Deutsch-Französische Grenze bei der Schlucht (1139 Meter ü. d. M). Zollämter” [Franco-German border at the Schlucht (1,139 m above sea level). Customs offices]. A shot dwells on the German boundary post standing 1,139 meters above sea level, which, for the French, symbolises the annexation of the “lost provinces”. About three meters high, a disc with the imperial eagle against a white, red-framed background resting on its top, it proclaims German sovereignty: Deutsches Reich. Thousands of other boundary posts were installed by the German authorities from 1889 onwards (chapter 2). A German police officer stops a group of tourists who want to cross the border, while German customs officers complete a few formalities. On the other side, a tourist’s bike is being controlled by two French customs officials. In this respect, this is an exceptional document: it is indeed the only video source showing the control of the French-German border (chapter 4).

Unfortunately, the ascent to the Hohneck is not filmed. However, the landscape of the summit is the highlight of the fourth part, „Auf der Spitze vom Hohneck (1361 Meer ü. d. M.)” [At the top of the Hohneck (1,361 m above sea level)]. Once they have reached the top, tourists choose from a selection of postcards, which they buy at Philippe Bernez’s inn in order to share their hiking experience. They can also use the orientation table that was installed by the Club alpin français, as the Hohneck is, for the most part, located on French territory. From the top, if the weather is fine, one can overlook the whole Alsace plain (chapter 6).

The last part, „Nach Gérardmer (französische Seite). Umsteigen. Der nächste Zug wartet schon“ [On the way to Gérardmer (French side). Changing trains. The next train is already waiting], follows the trolley journey from the Hohneck and Gérardmer. A railway connects these two locations via Retournemer and the Schlucht. Until shortly before World War I, there wasn’t any railway connection across the border, between the two slopes of the Vosges: the terminus of each line stopped at the border. Many tourists who, starting from Munster, climbed the Col de la Schlucht and the Hohneck on the eastern slope walked or drove down, or sometimes took the trolley on the western slope to Gérardmer, a spa and holiday town that had recently opened up for the then-emerging winter sports (chapter 6).

This film is an exceptional document in all respects, and allows to move straight to the issues of sovereignty and national identity constructions through local actors discussed here. It makes it possible to visualize several concrete border-crossing experiences, these experiences being made by individuals who precisely do not work for the French or German administrations.